A draft UCI document obtained by Escape Collective suggests the UCI plans to introduce an “Equipment Registration Process” (ERP) ahead of the 2023 Tour de France & Tour de France Femmes avec Zwift. The document, recently circulated among teams and manufacturers, is not a new set of regulations as much as a new process to ensure that existing rules in force are “properly adhered to.”

Nevertheless, the new regime significantly changes existing approval processes, and raises questions on how it will affect aspects like competitive fairness and innovation. The mid-season rollout also creates significant work for teams to comply with one team staff member describing the process as a “nightmare” to Escape Collective. The source conceded the concept is generally well received, but the extra workload, overheads, and resources required – just as teams are entering the heart of stage-race season – could prove problematic.

Why is the UCI rolling out a new process? The document references the UCI’s obligations to ensure “fair and equitable access to equipment” and the “particular importance in the context of the 2023 TDF and TDFF. The UCI references articles 1.3.003 which gives the UCI the right to introduce an ERP, and 1.3.006 or the so-called “commercialisation rule” that requires all equipment used in the sport to be publicly available for purchase.

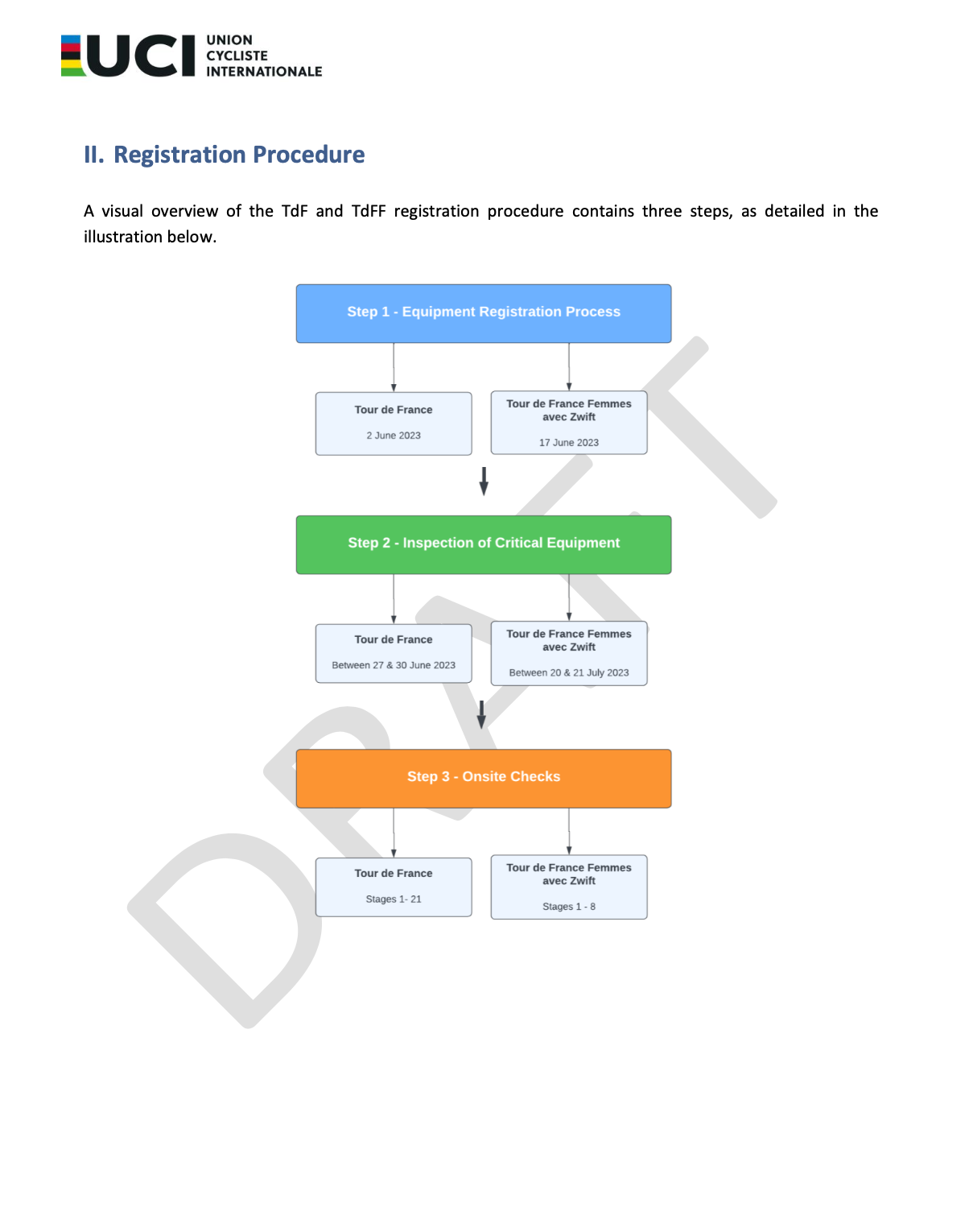

The ERP closely mimics the UCI’s “Track Equipment Registration Procedure” already in place ahead of the Paris 2024 Olympic Games. This new road equipment registration process, which the document suggests will initially only apply at the TDF and TDFF, and requires teams to pre-register all so-called “critical equipment” in advance of July’s races.

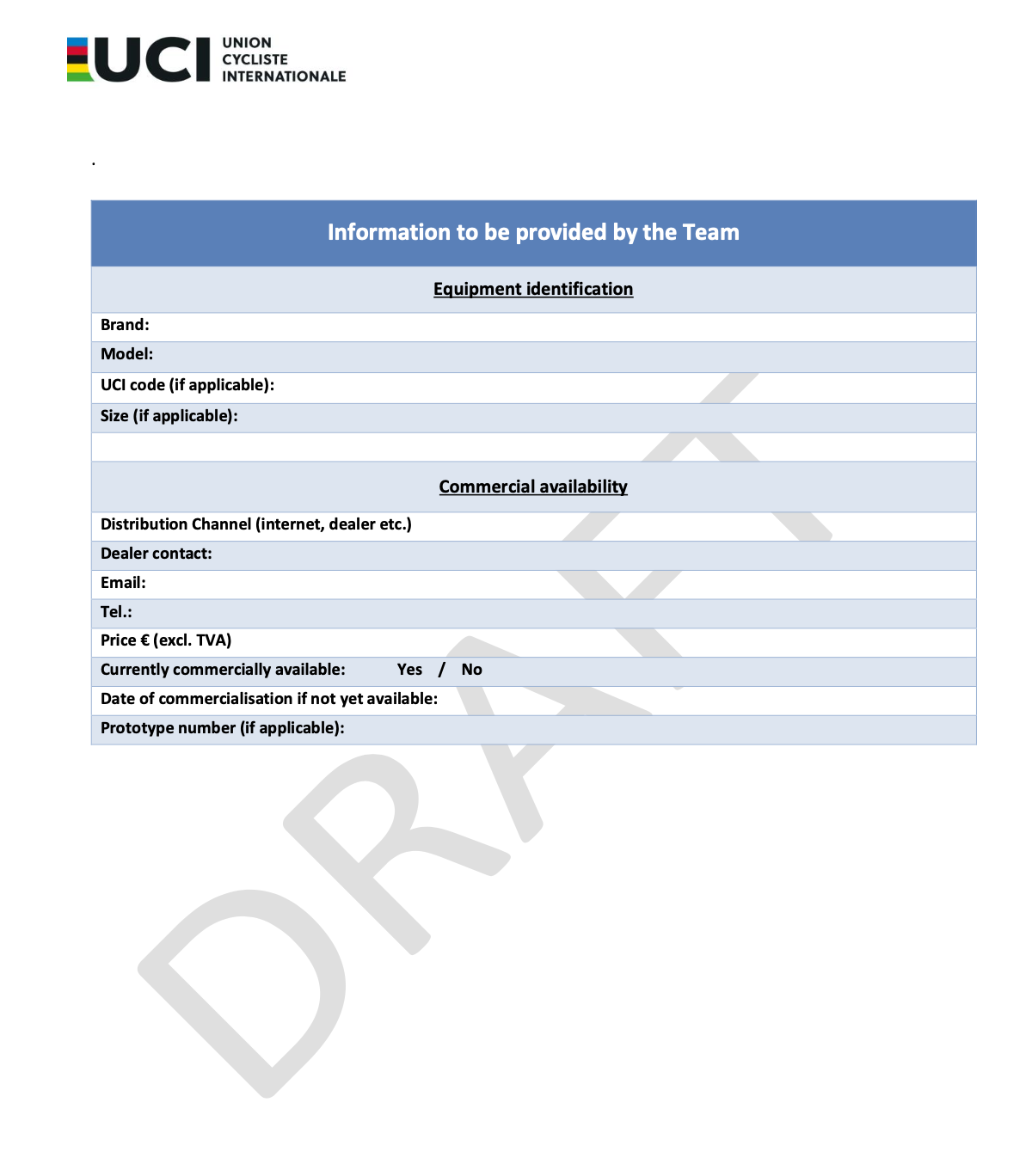

The UCI has deemed framesets (or modules), wheels, road and TT handlebars, TT extensions, clothing, and all helmets as “critical equipment,” all of which must be pre-registered on a UCI portal by the teams and submitted at the Grand Depart for assessment by UCI staff. While frames and wheels have required approval for years already, it’s these additional elements that had one manufacturer describe the proposal with unpublishable language.

“The frame approval is a known quantity, but now with bars, stems, clothing, etc., we can register it all and the UCI tell us we can’t use something just days before the Tour,” said the manufacturer, who spoke with Escape Collective on condition of anonymity.

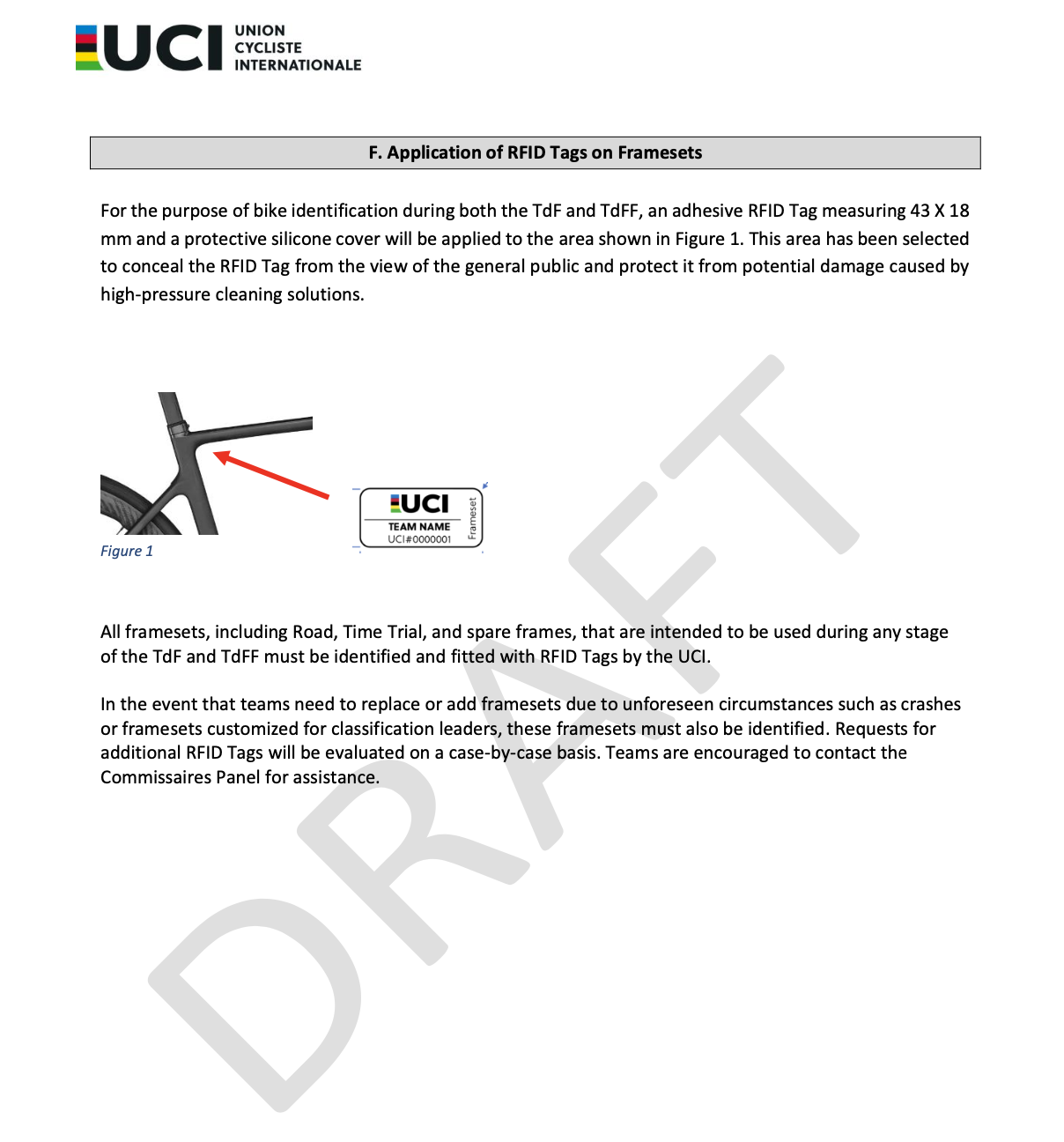

All registered equipment is then subject to inspection at the Grand Departs between June 27-30 for the men and July 20-21 for the women. It is at this point that “all framesets intended to be used at the TdF and TdFF must be presented for RFID tagging.” The UCI has deemed presenting “one item per model line” sufficient for all other critical equipment. The document details the inspection process, which includes scans, measuring, weighing, and photographing all equipment.

Upon passing these pre-Tour inspections, the UCI plans to apply a Radio Frequency Identification (RFID) tag to every frame teams wish to use during the Tour. The document explains the RFID is “for the purpose of bike identification during both the TdF and TdFF”, and will be attached on the underside of the top tube both to “conceal the RFID Tag from the view of the general public and protect it from potential damage caused by high-pressure cleaning solutions.”

It is not clear why the UCI wants the tags concealed from public view, but the document dictates that all frames, including road and time trial, must be inspected and tagged by UCI officials. If teams need to add framesets or replace tags due to crash damage or other cause, the document dictates that “requests for additional RFID Tags will be evaluated on a case-by-case basis.”

Undoubtedly, this will create additional work for teams and manufacturers in what is an already busy period in the build-up to the biggest races of the season, not to mention the extra work for the UCI on the ground. In fact, the document, dated the beginning of April, dictates all teams must register all their equipment via the “Online Registration Platform” by June 2 for the men’s teams and June 17 for the women’s. The UCI will allow teams to share logins with manufacturers, but the teams are ultimately responsible for all registration and should any failings occur it is the teams that will feel the hurt of any penalties.

The document is very clear in stating, “any Critical Equipment that is not registered via the Online Registration Platform (Step 1) will not be permitted for use during the TdF and TdFF.”

From then, the UCI will conduct random on-site checks during both races to ensure teams are using only the critical equipment that was pre-registered and approved.

The intention of the new Equipment Registration Process seems clear. The UCI wants to ensure all equipment used in the TDF and TDFF complies with the regulations in place, both at the point of homologation (accelerated in this case, as this process is usually months/years in advance) and during competition.

Furthermore, it seems, the UCI wishes to restrict the top-funded teams’ ability to bring new and advantageous equipment to the biggest race of the season. While such new equipment is fascinating from a tech writer’s point of view, it likely adds considerable stress to the UCI’s job on the ground at the Tour. Theoretically, the Equipment Registration Process will ensure a mid-race disqualification – such as Jan Willem van Schip’s DQ at the 2021 Tour of Belgium due to the use of Speeco Breakaway handlebars the UCI deemed illegal – will not happen at the Tour. While we can argue if certain equipment should be illegal or not, we can all agree it’s better a rider is not disqualified from the Tour based on equipment use.

Whether this new process ensures “fair and equitable access to equipment” or simply introduces an additional hurdle the top teams and manufacturers can easily clear with additional resources (read money), leaving smaller teams further in their wake remains to be seen.

Furthermore, Escape Collective understands that each team’s register will be visible to other teams. Coupled with the stricter commercialisation rules, this might ensure the “access” the UCI desires all teams to have, but at the expense of those driving innovation. Will a team be as motivated to push the boundaries in pursuit of the latest gain, if another team can simply purchase said new development for use in the same race? Or, on the contrary, will such visibility promote waste as teams play bluff building and registering all manner of equipment it never plans to use?

While the document is a draft, it seems almost certain the UCI plans to introduce the ERP ahead of this year’s Tours de France. An RFID trial was conducted at the recent Tour de Romandie and teams are already planning to ensure compliance. Furthermore, the document clearly states the ERP will only apply at the 2023 Tour de France and Tour de France Femmes. Of course, even that is a significant lift, requiring teams and on-ground UCI officials to catalog, register, inspect, and tag every frame, wheel, handlebar, helmet, and piece of clothing across 44 teams in two races, which start in barely two months.

Who the F#%k is going to do all this work?

A team equipment manager

Escape Collective has requested comment from the UCI. While the UCI agreed to provide a statement on the new registration process, it had not done so at the time of publication. We’ll update the article with any response we receive.

What did you think of this story?